The Nation Review on Terrorism How the West Can Win

The contempo controversy over Israel'south announcement as "terrorist" six Palestinian nongovernmental organizations—including Al-Haq, a leading homo rights monitoring group that was the first of its kind in the Middle East when cofounded by Raja Shehadeh, who wrote for the Review virtually all this—reminded me of an essay written some thirty-five years ago by Edward Said. That article, titled "The Essential Terrorist," appeared in Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question, a 1988 collection edited by Said himself and Christopher Hitchens. Said's essay was originally a book review for The Nation—its bailiwick, in his words, "Terrorism: How the West Can Win, edited and with commentary, weedlike in its proliferation, by Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli ambassador to the United Nations." Said went on:

Unlike the wimps who take merely condemned terrorism without defining it, Netanyahu bravely ventures a definition: "terrorism" he says, "is the deliberate and systematic murder, maiming, and menacing of the innocent to inspire fear for political purposes." But this powerful philosophic formulation is every bit flawed every bit all the other definitions, non only considering information technology is vague near exceptions and limits but because its application and interpretation in Netanyahu'south book depend a priori on a unmarried axiom: "we" are never terrorists; it'south the Moslems, Arabs and Communists who are.

Oh, that Netanyahu: the ane who graduated from being a Beltway influencer on the new pseudo–social science of Terrorism Studies to get the leader of Israel'due south Likud Party, a five-term prime minister, and by far the dominant Israeli politician of the by quarter-century. His 3rd volume on the topic, Fighting Terrorism: How D emocracies Tin Defeat Domestic and I nternational Terrorists, was published (in the US) the year before his starting time term in government. Since and so, the opportunity to put theory into practice and define all resistance to State of israel's settlement and de facto annexation of Palestinian territories as terrorism has served him well. One imagines that, though now out of office and still facing abuse charges, he must draw some satisfaction from seeing his antiterrorism mandate applied by an Israeli politician ordinarily described as a centrist in the country's politics, the quondam army primary Benny Gantz.

Never listen that the dossier to dorsum this most recent proscription, reportedly based on intelligence gathered by Israel'southward domestic security agency Shin Bet, has been debunked. (The clue is surely in the word "dossier," which, from supposed evidence of Iraqi WMDs to frolics in Moscow's Ritz-Carlton, seems the standard receptacle for garbage research and hearsay nonsense.) In this case, the report on the alleged status of the half-dozen NGOs equally front organizations for the Popular Front end for the Liberation of Palestine, a banned leftist group, relied—according to +972 Magazine, on sight of a leaked re-create—on uncorroborated testimony from two accountants who had been fired for embezzlement from a different NGO. Officials for several of the European governments that were shown the material by the Israeli Strange Ministry building in an try to persuade them to sever ties with, and stop funding of, the NGOs have rejected it as worthless.

The problem remains, though, that governments the world over take come to rely on the rhetorical tactic of placing opponents in a special category of irredeemable enemies of the state and declaring them terrorists. But how, not to credit Bibi with too much, did the "powerful philosophic conception" that Said diagnosed iii-plus decades ago come into being?

*

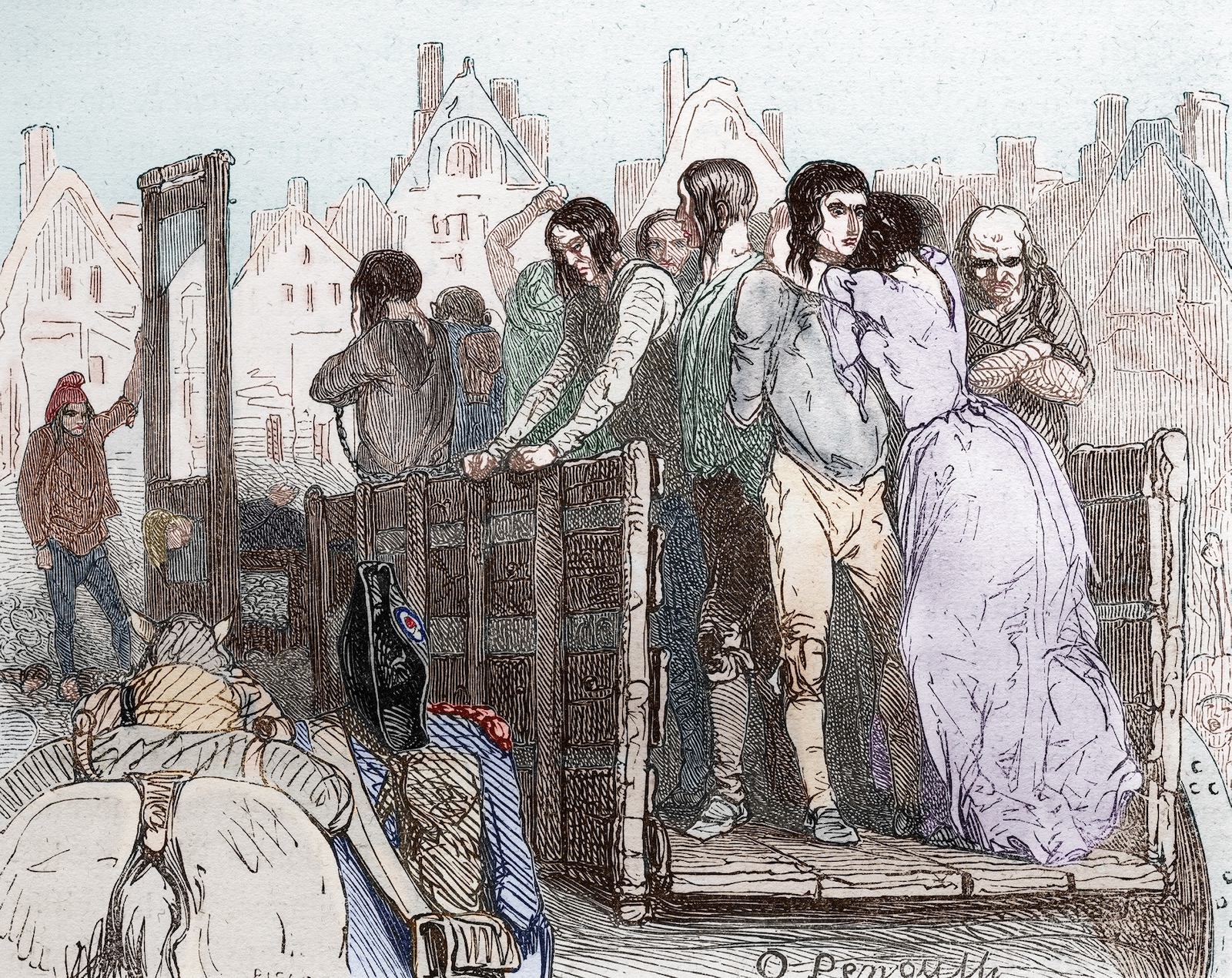

adoc-photos/Corbis via Getty Images

A colored 19-century engraving of prisoners beingness transported to the guillotine during the 1793–1794 Reign of Terror, France

This history begins, as so much does, with the French Revolution. The etymology seems to testify that "terror" (terreur) and "terrorism" (terrorisme) entered modern parlance with the bloody repressions of Maximilien Robespierre'south Commission of Public Safety (a prime Orwellianism avant la lettre) that saw thousands executed in the name of revolutionary justice from 1793 to 1794. What is central to this early on usage is that information technology refers very specifically to violence committed by the state against those it sees as guilty of subverting its dominance and aims. That definition, of terror as state violence, proved remarkably stable and enduring. It was the aforementioned definition that Leon Trotsky applied more a century later, in 1920, in a denunciation of the more moderate Austrian Marxist thinker Karl Kautsky. In characteristically polemical style, Trotsky wrote:

The State terror of a revolutionary class tin can be condemned "morally" just by a man who, as a principle, rejects (in words) every course of violence whatsoever—consequently, every war and every rising. For this one has to be merely and simply a hypocritical Quaker.

"But, in that case, in what practise your tactics differ from the tactics of Tsarism?" nosotros are asked, by the loftier priests of Liberalism and Kautskianism.

You exercise not empathise this, holy men? Nosotros shall explicate to you. The terror of Tsarism was directed confronting the proletariat. The gendarmerie of Tsarism throttled the workers who were fighting for the Socialist order. Our Extraordinary Commissions shoot landlords, capitalists, and generals who are striving to restore the backer gild. Do y'all grasp this…distinction? Aye? For us Communists it is quite sufficient.

A full-throated defense, in other words, of the Bolsheviks' right to use all the means at their disposal to hold onto state power by eliminating their enemies through terror. From Trotsky's lips to Stalin's ears. The gargantuan horror of the Stalinist Terror, at its summit in the tardily 1930s, may also have been the term'south historical apotheosis—fifty-fifty if it hardly marked the last instance of mass violence committed by the country. Merely we practise non, equally a rule, know Nazism'south atrocities by this discussion; nor has Terror with a capital T been commonly applied to such depredations of the postwar period—though worthy candidates come to mind, Mao's and Pol Pot'southward most immediately (at that place are plenty of non-Communist examples to choose from, besides).

What historical change, then, brought about the end of this ancien usage? The answer seems to lie in the period of decolonization after World War II, in which we see the meanings of terror and terrorism shift from violence inflicted past the state upon its citizenry to violence committed against the state by certain of its citizens. It is a remarkable transition: once the criminal perpetrator, the state now becomes victim of the crime. And by this sleight, the state gains the right to enact desperate measures by claiming cocky-defense in the name of public rubber (that roughshod phrase, again). What appears unmistakably true is that this reversal of semantic polarities—culminating in the dubious scholarship of Netanyahu and colleagues—could only have taken place through the Westward's experience of various postcolonial "emergencies." The essential terrorist, equally Said noted, must exist an enemy other who will bear the burden of this new meaning. This has manifested in so-called emergencies all over the world, from Malaya to Kenya to Algeria to Vietnam to Northern Republic of ireland.

Where in the earth might we look for this postcolonial realignment of the nature, and agents, of terrorism? My answer—there could be others—would be apartheid South Africa.

Consider this straightforward sequence of events. In 1950, the apartheid regime passed the Suppression of Communism Act. In 1960, South African police made the township of Sharpeville internationally notorious by firing upon a crowd of demonstrators—killing sixty-nine people and injuring another one hundred and eighty; amid the casualties were xx-nine children. The massacre was a turning bespeak in the anti-apartheid struggle: the 2 primary Black opposition groups, the Pan African Congress and the African National Congress, both presently decided to brainstorm armed resistance to the regime. Following the 1963 arrests of a dozen or so leading members of the ANC, on suspicion of conspiring to commit acts of demolition, the Rivonia Trial concluded with the sentencing of viii defendants to life imprisonment; amidst them Nelson Mandela. In 1967, South Africa passed the Terrorism Act, which sanctioned the detention without trial of anyone suspected to "endanger the maintenance of law and order."

South Africa is an instructive instance, peradventure the pivotal ane, because the apartheid state—relatively insulated from the common cold war conflicts taking identify elsewhere merely facing an opposition move entrenched in a Black majority that lacked any existent rights—chose to shift its criminalization of adversaries from charging them as Communists to imprisoning them as terrorists. Information technology was this legal innovation by apartheid lawyers and lawmakers that made terrorism not a crime of the state but a offense confronting the state. Every bit John Dugard, a police professor and so at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, wrote in 1978: "Although designed to combat terrorism, the Terrorism Act has itself become an musical instrument of terror."

The law offered a new template shortly taken up and imitated around the world. U.k. was an early on adopter, passing a string of antiterrorism statutes between 1974 and 1989, with some other raft enacted from 2000 to 2015; but countries as varied and far apart every bit Kingdom of belgium and Bangladesh, Turkey and Canada, Prc and New Zealand, take followed suit.

The legacy of antiterrorism in the United Kingdom provides particularly rich detail about the mechanism behind terror'due south altered pregnant. At the beginning of the Troubles, after the British Army had been deployed, ostensibly to quell violent unrest between nationalists and loyalists that followed protests by Northern Ireland's civil rights movement, a brigadier named Frank Kitson was dispatched to direct the armed forces operation. He had learned his craft, counterinsurgency, in the brutal colonial conflicts in Kenya and Malaya, and he now applied those tactics to Belfast and Derry against a resurgent Irish Republican Regular army (this is a tale Patrick Radden Keefe skillfully recounts in his 2018 volume Say Nothing). Simply while counterinsurgency was the soldiers' manual, antiterrorism was the Westminster politicians'.

Of no British leader over the course of the Troubles would this exist more emphatically then than Margaret Thatcher. For her, it was personal: the IRA had succeeded in assassinating her friend and mentor Airey Neave in 1979, the year she would become prime number minister, and the group very nearly succeeded in assassinating her 5 years later, in a bombing at a hotel hosting participants of the Conservative Party conference in Brighton. Her mantra throughout the 1980s was "Nosotros don't negotiate with terrorists." Indeed, later 1988 this ban was extended fifty-fifty to hearing them—that was the year her government enacted a police force prohibiting broadcasters from transmitting the voices of Republican leaders like Sinn Fein's Gerry Adams, which led to the faintly surreal workaround by TV and radio newsrooms of employing actors to read their words. The hypocrisy of Thatcher'southward stance has since been exposed by the release of official papers that make information technology perfectly articulate that on a number of occasions she certainly did negotiate with terrorists.

That niggling awkwardness also highlights ane of the issues that ascend when governments attempt to identify state opponents beyond the premises of acceptable political actor and interlocutor: it's embarrassing to have to reverse. Subsequently Ronald Reagan joined Margaret Thatcher in accepting the apartheid regime'south designation of the ANC equally a terrorist organization, in 1988 the U.s.a. Section of Defense added Mandela and the ANC to a list of "fundamental regional terrorist groups." Mandela was released from Robben Island just two years later, yet he remained on a US terrorism watchlist until 2008—xiv years after he became S Africa's first post-apartheid president, a menses in which he met with every sitting American president.

The United States has, of course, made its own, typically infrequent contribution to the twenty-showtime-century definitions of terror and terrorism. The "war on terror" that President George W. Bush declared to Congress shortly after the September eleven, 2001, attacks took what had previously been the state's struggle confronting local armed resistance or anticolonial insurgents to a new, global domain. Formerly, per Said'due south schema, governments had used "terrorist" to outlaw particular opponents that resorted to violence, groups such as the PFLP and the Basque ETA that claimed legitimacy on political or nationalist grounds (though sometimes conditioned by ethnic or religious minority condition). In contrast, the US later on September 11 arrogated to itself the correct to use war machine force anywhere in the world, where alliances or client governments permitted, against non-state actors, who were thus a priori terrorist adversaries. (This "state of war" also created a pretext, which circumvented international police, for detaining and torturing "enemy combatants" captured, or kidnapped, by the US and its surrogates.)

Generally, this has been achieved nether the rubric of fighting "radical Islamic [sic]" groups in any theater of operations they happen to be. Given that the US's principal weapon in this war has, in practice, become the drone-launched missile, for all intents and purposes at that place is little oversight or scrutiny—either through Congress or amongst the wider American public—of whom the US has targeted as terrorists by this means. Only on rare occasions, when, usually for other reasons, there is shut media attention, is whatsoever light shone on whether lethal violence has been rained down on anyone even vaguely meeting the open-ended US designation. Such a case occurred on Baronial 29, when a U.s.a. drone attacked killed x Afghan civilians mistakenly identified by the US military as members of ISIS-Thou. According to the independent investigative and monitoring grouping Airwars, in the twenty years of the "state of war on terror," at least 22,679 civilians (and perchance more than twice that number) have died equally victims of Us drone strikes.

It might seem reasonable to adapt and update Dugard'due south words: although designed to combat terrorism, the U.s. Patriot Human action and the Authorization for Employ of Military Force have themselves get instruments of terror. That argument—attempting to put the Terror back in terror—was precisely what Noam Chomsky tried to achieve with his essay in Said's 1988 collection. Despite its rather lugubrious title, "Middle Due east Terrorism and the American Ideological System," Chomsky's was a decent effort simply its relative lack of influence—compared with, say, Netanyahu's—rather suggests that returning terror to its Robespierrean root is a quixotic venture. It has been easier, it turns out, to welcome erstwhile terrorists into government and brand them state officials (albeit the word "sometime" has had to do a lot of work there).

*

We have reached, then, a indicate in the etymology of terror at which governments take assumed the correct to designate whatsoever specific person or grouping, literally anyone they don't similar, as terrorists. By i new standard for terrorism, it can employ to human rights lawyers and researchers who irritate authorities officials, considering to decry state violence has become itself a terrorist criminal offence. By the other new standard, information technology can utilise to anyone who happens to be in the wrong place at the wrong time—the time and place beingness lethally side by side to wherever the United states of america is hunting "war on terror" adversaries.

My initial example came from Israel, but it'southward worth noting that the United states now uses both standards—one for enemies strange, the other for enemies domestic. The latter has found a new currency in recent controversies over who is a domestic terrorist. For several years after 2001, the definition of domestic terrorism seemed relatively stable and commonsensical to about Americans: information technology applied to self-radicalized Muslims. (This as well led to some very troubling over-surveillance and entrapment plots directed at American Muslim communities.) Now, however, there is a push to redefine domestic terrorism to include, or "mean," white nationalist and white supremacist groups and antigovernment militia organizations. That is an understandable liberal reflex—to redirect regime law enforcement and intelligence agencies from inappropriate targets toward more "deserving" ones—but it leaves intact, even reinforces, the state's power to define enemies in the name of public safety. (Information technology is not hard to imagine how a simple change of The states administration might shortly encounter Antifa, even Black Lives Affair, placed within the framing of domestic terrorism.)

It could be that the entire rhetorical gambit of terror is reaching the limits of its coherence, a reductio advertising absurdum, the end of the semantic road. That would be an optimistic reading of this latest turn in the story. Given both their inertia and their aversion to humiliating nigh-faces, country institutions endow their designations of terrorism with a long half-life. If information technology took some 150 years to recast the pregnant of terror from something malign governments did to their people into violence committed by malign people to outrage governments, how long might it be before the poles reverse again? And past what historical agency?

It may exist simpler and easier to banish the tainted term from the lexicon of public discourse. What should be apparent today is a charge then discredited, so empty of existent meaning, that the forcefulness of moral condemnation information technology once commanded ought to rebound on those who would use information technology.

Source: https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2021/11/17/the-etymology-of-terror/

0 Response to "The Nation Review on Terrorism How the West Can Win"

Enregistrer un commentaire